October often feels like the garden’s closing chapter. The roses fade, the nights turn colder, and many gardeners put their tools away until spring. But I’ve come to see this season differently. For me, October is the start of next year’s garden. Cold-hardy annuals love the chill. They settle into the soil in fall, hold steady through winter, and explode into growth the moment spring light returns.

These flowers are the bridge between seasons. They carry the garden from the last bulbs of early spring to the first wave of summer blooms, adding color and texture when borders would otherwise look bare. Over the years, I’ve tested plenty of “cold lovers” that didn’t live up to their name. But the true hardy annuals—plants like ammi, cerinthe, and calendula—have proven themselves, weathering frosty nights and rewarding me with reliable, early flowers.

The best part is that nature does much of the work. Winter cold stratifies the seeds, roots grow quietly under the surface, and by spring the plants are already ahead of the game. The result is earlier color, sturdier growth, and a garden that looks alive weeks before tender annuals even leave the seed tray.

If you’ve ever wanted a head start on spring, these are the flowers that deliver. Here are ten cold-hardy annuals I plant every October for a garden that wakes up strong and keeps blooming into summer.

Why You Should Grow Hardy Annuals

Every year I’m reminded why hardy annuals earn their place in the garden. For one thing, they spread out the work. Planting some in fall takes the pressure off spring, when it feels like everything needs to be done at once. By the time warmer weather arrives, these early sowings are already settled in and growing strong.

I also love how naturally they fit the season. Hardy annuals are at their best in cool weather, blooming just as the bulbs fade and long before summer flowers wake up. Without them, there’s often a gap in the garden—a lull between tulips and daffodils bowing out and the zinnias and cosmos taking over. With them, there’s no empty space, only a continuous flow of color.

Most of all, I grow hardy annuals because they make spring feel fuller, earlier, and more generous. They carry the garden through that awkward in-between and give me blooms weeks before I’d otherwise expect them. In a busy gardening year, that kind of gift is hard to turn down.

Why Plant Hardy Annuals in Fall?

Planting hardy annuals in fall feels almost counterintuitive—most of us are used to sowing in spring. But these cool-season flowers are built differently. Their seeds need a dose of cold, called stratification, to break dormancy. By sowing in fall, you’re letting nature handle that process for you. The winter chill does the work, and the seeds germinate at exactly the right time come spring.

There’s another advantage: fall-sown hardy annuals develop strong root systems long before they’re asked to flower. Instead of racing against rising temperatures in spring, they sit quietly through winter, establish themselves, and then surge into bloom as soon as the days lengthen. The result? Taller plants, longer stems, and a much bigger flush of flowers compared to spring sowings.

In my own garden, I’ve noticed that fall-planted larkspur, nigella, and bells of Ireland not only bloom earlier, they keep flowering longer into the season. They’re simply sturdier plants, less bothered by pests, dry spells, or a sudden heatwave. It’s as if that winter rest gives them a resilience you can’t replicate with a late start.

Protecting Hardy Annuals from Extreme Cold

Even the toughest cool flowers can get caught off guard when the weather turns harsher than expected. A sudden freeze doesn’t mean disaster, though—it just calls for a few quick tricks.

I’ve found that a deep watering the night before cold weather makes a big difference. Damp soil holds onto warmth and protects the roots better than dry ground. On the coldest nights, I’ll pull out a lightweight frost cloth, or even an old bedsheet, and drape it over hoops to keep it from touching the plants. That thin barrier creates a pocket of warmer air underneath, often just enough to carry them through.

The truth is, hardy annuals don’t need to be babied. They’re bred for frosty nights and fluctuating temperatures. As long as you’ve sown them at the right time for your zone, they’ll take most of what the season throws at them. A little extra protection now and then just helps them come out stronger on the other side.

Cold-Tolerant Annuals I’m Adding to My Garden This Fall

I’ve tested plenty of annuals to see which ones truly stand up to cold, and a few have become my go-to choices year after year. Some so-called “cold lovers” disappoint—Senetti, for instance, collapsed after the lightest frost—while others surprise me with their toughness. Petunias lasted longer than expected, and Angel Wings (Senecio candicans) has proven almost indestructible, still looking fresh after hard freezes.

Here are 15 of the best cold-tolerant annuals I count on year after year to deliver gorgeous blooms long before the heat lovers take their turn.

1: Iceland Poppies (Papaver nudicaule)

Iceland poppies are proof that some of the most delicate-looking flowers are also the toughest. Their tissue-thin petals in shades of lemon, coral, tangerine, and white practically glow in spring sunlight, yet the plants themselves are remarkably cold-hardy. I’ve found that they perform best when sown in October—the winter chill acts as natural stratification, helping the seeds break dormancy and emerge strong when spring arrives.

Because of their fine taproot, poppies don’t like to be moved. Direct sowing outdoors is the most reliable way to grow them, scattering seed on well-drained soil and letting frost and snow do their quiet work. In Zones 7–11, fall sowings overwinter beautifully; in colder regions, you can try fall sowing with a layer of protection, or wait until very early spring to mimic the same effect. Some gardeners start seed indoors after a few weeks of refrigeration, but I find plants are always sturdier when grown in place.

Once they settle in, Iceland poppies reward you with weeks of bloom from late spring into early summer. Harvested in the bud stage, the flowers last far longer in a vase than you might expect, making them every bit as valuable indoors as they are in the garden.

- Zones: 7–11 (grown as an annual elsewhere; fall or very early spring sowing in Zones 3–6)

- Size: 12–24 inches tall × 8–12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; well-drained soil; very cold-hardy; best direct sown outdoors; avoid transplanting due to taproot

2: Linaria (Linaria maroccana)

Linaria, sometimes called toadflax, may not get the attention it deserves, but once you grow it, you’ll never want to be without it. Its airy stems carry dozens of small, snapdragon-like blooms in a rainbow of colors—from pastel pinks and yellows to vibrant purples and reds. Planted en masse, linaria creates a soft, meadow-like effect that feels both whimsical and effortless, perfect for filling gaps in the spring garden.

This is a hardy annual that responds beautifully to fall sowing. Scatter seed in October over prepared soil, and the plants will germinate, overwinter as sturdy rosettes, and leap into bloom by mid to late spring. In Zones 7–11, linaria overwinters reliably outdoors, while in colder climates, you can mimic fall sowing by planting very early in spring. Because the seedlings are fine and threadlike, direct sowing is usually best, though they will tolerate gentle transplanting if started in trays.

Once it begins to flower, linaria just keeps going, especially in cooler weather. It’s wonderful in bouquets, where its delicate stems weave beautifully among larger blooms, but I also love it left to self-sow—once established, it often pops up again in the garden, gifting you with surprises year after year.

- Zones: 3–10 (fall sowing in mild climates; very early spring sowing in colder zones)

- Size: 12–24 inches tall × 6–12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun to light shade; average, well-drained soil; best direct sown; will often self-seed in place

3: Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium)

Feverfew is one of those hardy annuals that quietly earns its place in the garden year after year. With its sprays of small, daisy-like white flowers and soft green foliage, it’s both charming in a border and invaluable as a cut flower. Despite its delicate look, feverfew is remarkably cold-tolerant, thriving when sown in the cool of autumn. I’ve found that October sowings lead to sturdy plants that settle in over winter and then bloom generously by late spring.

The seeds germinate easily but are best sown where they’ll grow. Direct sowing outdoors works beautifully in Zones 7–11, where seedlings handle frost without issue. In colder climates, you can try fall sowing under a light protective mulch, or start indoors in early spring if winters are severe. If sowing inside, surface sow onto moist soil—feverfew needs light to germinate—then transplant carefully to avoid root disturbance. Once established, it thrives in sun and ordinary, well-drained soil, needing little more than occasional watering during dry spells.

In the vase, feverfew is a florist’s favorite, adding lightness and texture to arrangements. In the garden, it weaves between roses, foxgloves, or larkspur, softening their lines and tying everything together with its cheerful, long-lasting blooms.

- Zones: 7–11 (annual elsewhere; fall sowing possible in Zones 3–6 with protection)

- Size: 18–24 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; well-drained soil; cold-hardy; direct sow in fall or start indoors in early spring; needs light for germination

4: Bells of Ireland (Moluccella laevis)

Bells of Ireland bring an unexpected freshness to the spring border. Their tall, upright stems are lined with lime-green, bell-shaped calyces that look as though they’ve been strung together for a celebration. In a garden filled with soft pinks, purples, and blues, their vivid green creates contrast and drama—while in bouquets, they provide height and a striking backdrop for more colorful blooms.

October is the perfect time to sow them. The seeds benefit from cool weather to break dormancy, and fall sowing allows nature to take care of that for you. Bells of Ireland can be started indoors in individual pots, but they’re happiest when direct sown outdoors where they’ll grow undisturbed. Give them a bright, open spot and soil that drains well, and they’ll reward you with tall, architectural stems that look like living sculpture by early summer.

- Zones: 7–11, grown as an annual elsewhere

- Size: 24–36 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; rich, well-drained soil; sow in fall for best germination; direct sow preferred but can be started indoors in small pots

5: Love-in-a-Mist (Nigella damascena)

There’s a kind of magic to Love-in-a-Mist. The flowers themselves—sky blue, blush pink, or pure white—are beautiful, but it’s the finely cut foliage that gives them their charm, like each bloom is floating inside a cloud. I’ve always thought nigella is best appreciated up close, where you can see the star-shaped flowers framed in their delicate green halos.

As a hardy annual, nigella thrives on cold. I like to sow it in October and leave the rest to winter—the seeds use the chill as a signal to germinate strongly when spring arrives. Because the plants form a taproot, direct sowing outdoors is by far the easiest and most reliable method. In Zones 7–11, seedlings overwinter happily. In colder regions, you can still try fall sowing with a bit of mulch for protection, or scatter seed very early in spring so it catches the tail end of winter cold.

By late spring, the garden is filled with their soft colors, and as the blooms fade, they form papery, balloon-like seed pods. I often leave some in the border for their sculptural look, and save a few for drying—they’re every bit as decorative as the flowers.

- Zones: 7–11 (grown as an annual elsewhere; fall or early spring sowing in Zones 3–6)

- Size: 12–24 inches tall × 8–12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; well-drained soil; cold-hardy; direct sow outdoors for best results; dislikes being transplanted

6: Snapdragons (Antirrhinum majus)

Snapdragons are often treated as tender annuals, but in reality they’re far tougher than most people realize. In many climates, they’ll overwinter with ease if planted in fall, sending roots deep into the soil while the rest of the garden sleeps.

By spring, they leap into growth, flowering weeks earlier than spring-sown plants and often carrying their blooms right into early summer.

October sowings give snapdragons a head start that shows in both vigor and bloom quality. In Zones 7–11, they can be sown directly outdoors or started in trays and planted out before the first hard frost. In colder zones, start seed indoors in late summer or very early fall, grow them on under protection, and transplant as soon as the soil is workable in spring. With a little cover in harsher climates, snapdragons can surprise you with just how resilient they are.

Beyond their toughness, snapdragons are classics for a reason. Their upright spikes come in every color imaginable, from bold jewel tones to soft pastels, and their long vase life makes them staples for cutting gardens. Sow a mix of varieties for height, fragrance, and continuous color in both borders and bouquets.

- Zones: 7–11 for fall planting; grow as cool-season annuals in Zones 3–6

- Size: 12–36 inches tall × 8–12 inches wide (depending on variety)

- Care requirements: Full sun; fertile, well-drained soil; start indoors or direct sow; benefit from pinching to encourage branching

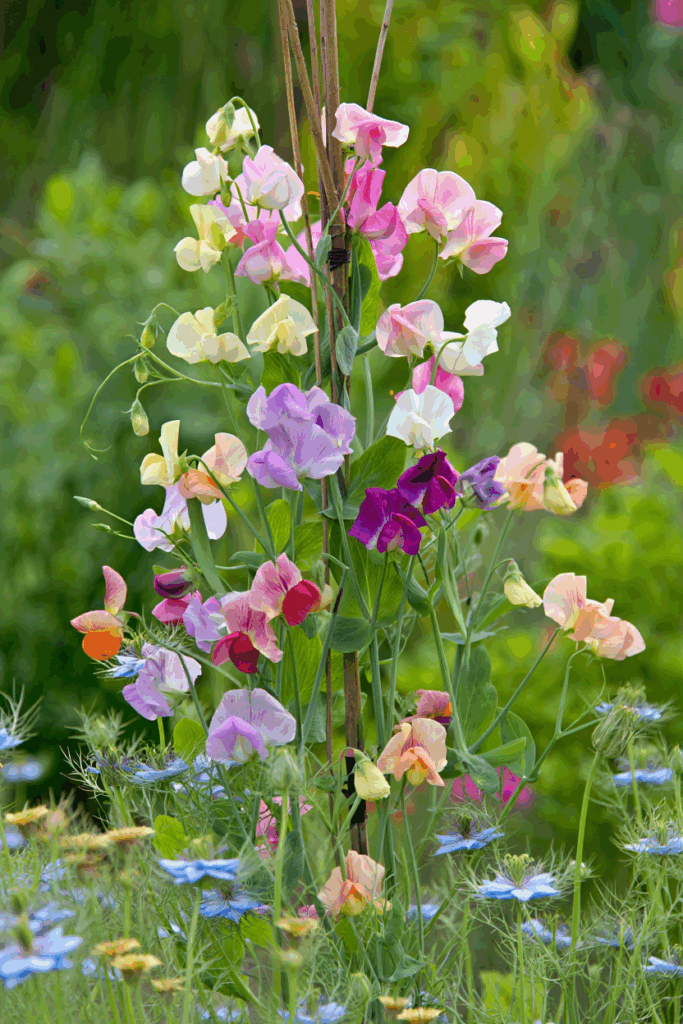

7: Sweet Peas (Lathyrus odoratus)

Sweet peas are the stars of any spring garden—climbing vines that drip with ruffled blossoms in shades from soft pastels to deep jewel tones. Their fragrance is unforgettable, filling the air with the scent of old-fashioned gardens.

As hardy annuals, sweet peas thrive on cool weather. Sowing in October allows seedlings to settle in through winter, giving them stronger roots and more abundant blooms in spring. In Zones 7–11, direct sowing outdoors works best; in colder climates, start seed indoors in deep pots in late winter, then plant out as soon as the ground can be worked. Because they dislike shallow containers, root trainers or tall modules are ideal.

With steady moisture, fertile soil, and a simple trellis or wigwam for support, sweet peas will reward you with weeks of bloom. Pick them often—the more you cut, the more flowers they’ll produce.

- Zones: 7–11 (annual elsewhere; sow indoors in late winter for colder regions)

- Size: Vines 4–6 feet tall with support

- Care requirements: Full sun; rich, well-drained soil; cold-hardy; direct sow in fall where winters are mild, or start indoors in deep pots

8: Euphorbia (Euphorbia oblongata)

Euphorbia may not be the first plant you think of when planning a flower border, but once you grow it, you’ll wonder how you managed without it. Its fresh green bracts bring a luminous quality to spring arrangements, providing the perfect backdrop for brighter flowers like sweet peas, larkspur, and poppies. In the garden, it’s equally valuable, weaving a soft green thread through the border and holding everything together.

As a hardy annual, euphorbia thrives when sown in October, settling in through the cold months before bursting into growth as spring warms. Direct sowing works well in Zones 7–11, though it can also be started indoors in individual pots if needed. Once established, it’s remarkably resilient, tolerating cool nights, variable soils, and light frost with ease. Just remember to wear gloves when handling the milky sap.

- Zones: 7–11 (annual elsewhere)

- Size: 24–36 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun to partial shade; average, well-drained soil; cold-hardy; direct sow in fall or start indoors in pots

9: Bachelor’s Buttons / Cornflower (Centaurea cyanus)

I’ve always believed no spring garden feels complete without a drift of bachelor’s buttons. They’re the kind of hardy annual that prove their worth every year—cold-tolerant, resilient, and willing to flower where many others falter. Sown in October, the seedlings sit patiently through frost and freezing nights, holding steady until the soil begins to warm. By late spring, they’re covered in their signature blooms—intense sky-blue most often, but also soft pinks, purples, and whites if you grow a mix.

These flowers aren’t just pretty; they’re practical. They germinate easily, don’t demand rich soil, and once established, they withstand dry spells without fuss. I recommend direct sowing in fall for the strongest, earliest plants, though they’ll still perform if started in modules indoors. As cut flowers, they last surprisingly well in the vase; in the garden, they’re invaluable for filling gaps and softening the edges of borders. For me, bachelor’s buttons embody what hardy annuals are all about: strength, simplicity, and a burst of beauty that comes just when the garden needs it most.

- Zones: 7–11, grown as an annual elsewhere

- Size: 12–24 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; well-drained soil; cold-hardy and frost-tolerant; best direct sown in fall for earliest blooms

10: Queen Anne’s Lace (Ammi majus)

Queen Anne’s Lace is one of the classic hardy annuals that actually prefers a period of cold before it germinates. The seeds benefit from what’s called cold stratification—exposure to chilly, moist conditions that naturally break dormancy. That’s why October sowing works so well. When sown outdoors in fall, the seeds rest in the soil all winter, then sprout as soon as temperatures begin to warm in spring.

This plant is best grown by direct sowing outside, since its long taproot does not handle transplanting well. Simply scatter the seed into prepared beds in fall and let winter weather do the work. In Zones 7–11, it will overwinter easily; in colder climates, you can still try fall sowing, but gardeners in Zones 3–6 often have better luck sowing in very early spring (as soon as the ground can be worked) to mimic the same effect. If you must start indoors, chill the seeds in a moist paper towel in the refrigerator for 2–3 weeks before sowing in pots, but expect weaker results compared to direct outdoor sowing.

Once established, Queen Anne’s Lace is low-maintenance—thriving in full sun, average soil, and cool spring weather. The lacy white umbels bloom from late spring into summer and make one of the finest fillers for cut flower arrangements.

- Zones: 7–11 (grown as an annual elsewhere; in Zones 3–6 sow in fall or very early spring)

- Size: 36–48 inches tall × 12–18 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; average, well-drained soil; benefits from cold stratification; best sown directly outdoors in fall

11: Annual Baby’s Breath (Gypsophila elegans)

Annual baby’s breath is the definition of effortless charm. Its tiny white flowers scatter across fine, branching stems, creating a soft mist that drifts through borders and bouquets alike. I think of it as the quiet background music of the garden—it never steals the show, but everything looks better with it there.

Despite its delicate look, baby’s breath is a true cold-hardy annual. Sown in October, the seed rests through winter and germinates as soon as conditions allow in spring. Because it forms a fine taproot, it is best direct sown outdoors where it will grow. In Zones 7–11, fall sowings overwinter with ease; in colder climates, gardeners often sow very early in spring to achieve the same effect. Baby’s breath doesn’t ask for much—just a sunny site and well-drained soil.

By late spring, it fills the border with its airy texture and is invaluable in the cutting garden, where it lightens and softens every arrangement. Whether woven among roses, nestled beside larkspur, or simply left to drift in its own cloud, baby’s breath brings a kind of easy elegance only a hardy annual can.

- Zones: 7–11 (annual elsewhere; sow in very early spring in Zones 3–6)

- Size: 12–24 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; light, well-drained soil; cold-hardy; best direct sown outdoors in fall; dislikes transplanting

12: Pincushion Flower (Scabiosa atropurpurea)

There’s a playful charm to pincushion flowers. Each bloom is a perfect little dome, dotted with stamens that look like pins, perched on long, airy stems that sway in the lightest breeze. In colors ranging from soft lavender and blush to deep wine, they bring movement and personality to spring borders, and they’re irresistible as cut flowers.

Though delicate in appearance, scabiosa is a hardy annual that relishes the cool side of the season. I like to sow it in October, when the soil is still workable but nights are cool. Seedlings settle in over winter, then leap into growth as soon as days lengthen. In Zones 7–11, fall sowing outdoors is simple and effective; in colder climates, sow indoors in late winter and transplant carefully once the soil can be worked. With regular cutting or deadheading, pincushion flowers will keep blooming well into summer.

- Zones: 7–11 (annual elsewhere; sow indoors in late winter for colder zones)

- Size: 24–36 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; well-drained soil; cold-hardy; best direct sown in fall; cut or deadhead regularly to extend bloom

13: Calendula (Calendula officinalis)

If there’s one hardy annual I’d never be without, it’s calendula. Sometimes called “pot marigold,” this cheerful flower has been grown in cottage gardens for centuries—valued not just for its bright orange and golden blooms, but also for its usefulness in the kitchen and apothecary. I love how it lights up the garden on gray spring mornings, its petals opening with the sun as if to remind you that warmer days are on their way.

Calendula is a true cold-tolerant annual, thriving in the cool, damp weather of spring. When sown in October, seedlings nestle through winter and are ready to burst into bloom as soon as the season turns. In Zones 7–11, fall sowing outdoors is simple and reliable. In colder regions, you can scatter seed in very early spring, since calendula germinates best in cool soil. Indoors sowing works too, but I find direct sowing nearly always produces sturdier plants.

Once established, calendula is remarkably forgiving. Give it sun and reasonably fertile, well-drained soil, and it will bloom steadily into summer if you keep cutting or deadheading. And as a bonus, its petals are edible—perfect for tossing into salads or drying for teas and herbal remedies. To me, calendula is the very definition of an old-fashioned garden flower: beautiful, useful, and delightfully easy to grow.

- Zones: 7–11 (annual elsewhere; sow in very early spring in Zones 3–6)

- Size: 12–24 inches tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; moderately fertile, well-drained soil; cold-hardy; best direct sown outdoors in fall; cut or deadhead to extend bloom

14: Breadseed Poppies (Papaver somniferum, Peony-flowered Types)

Breadseed poppies may be rugged, cool-season annuals, but when the peony-flowered forms open, they look nothing short of decadent.

With huge, ruffled blooms in shades of pink, plum, and scarlet, they bring a touch of drama to the spring garden—proof that hardy annuals don’t have to be plain or understated.

Even better, they’re remarkably cold-tolerant, thriving on fall sowings that allow roots to anchor before winter settles in.

Because they form a strong taproot, breadseed poppies are best direct sown where they’ll grow. Scatter seed in October on prepared, well-drained soil, and let the chill of winter stratify them naturally. In Zones 7–11, they overwinter reliably; in colder regions, a layer of mulch or frost cloth can help seedlings survive. Gardeners in northern climates can also mimic fall sowing by planting very early in spring, just as the soil becomes workable.

The flowers are fleeting but unforgettable, and once petals drop, the seedpods take over as sculptural accents in the garden. They’re excellent for drying, saving seed, or simply leaving in place for texture well into summer.

- Zones: 3–9 (direct sown in fall for mild climates; very early spring sowing in colder zones)

- Size: 2–4 feet tall × 12–18 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; lean, well-drained soil; direct sow only, as seedlings resent disturbance

15: Larkspur (Consolida ajacis)

Larkspur is the classic example of a hardy annual that actually needs the cold to do its best. The tall, graceful spires in shades of purple, pink, and white look delicate, but these flowers thrive in chilly weather and resent heat. In fact, their seeds require a period of cold stratification to germinate properly—making October the ideal time to sow them.

By planting in fall, you’ll ensure strong, early-blooming plants that bring height and elegance to the spring garden.

Because larkspur forms a long taproot, it’s best direct sown where you want it to grow. Scatter the seed over well-drained soil in October, and let winter’s natural chill break dormancy. In Zones 7–11, fall sowings overwinter reliably and bloom by late spring. In colder regions, you can mimic the same process by refrigerating seed for a few weeks and sowing very early in spring, as soon as the soil can be worked.

Once established, larkspur adds vertical drama to borders and cutting gardens alike. The flowers last well in arrangements, and successive sowings can extend the bloom window into early summer before heat sets in.

- Zones: 3–10 (fall sowing in mild climates; early spring sowing in colder zones)

- Size: 2–4 feet tall × 12 inches wide

- Care requirements: Full sun; alkaline to neutral, well-drained soil; direct sow for best results; dislikes transplanting

Written By

Amber Noyes

Amber Noyes was born and raised in a suburban California town, San Mateo. She holds a master’s degree in horticulture from the University of California as well as a BS in Biology from the University of San Francisco. With experience working on an organic farm, water conservation research, farmers’ markets, and plant nursery, she understands what makes plants thrive and how we can better understand the connection between microclimate and plant health. When she’s not on the land, Amber loves informing people of new ideas/things related to gardening, especially organic gardening, houseplants, and growing plants in a small space.

Thank you for all this detail and selection of what truly works! Now I understand why my Feverfew planted mid-May didn’t germinate!! Question: will most of these fade by the time to plant my direct sown annuals, specially Zinnias Cosmos, Celosia, Dahlias? Can I use the same beds (rotate out the hardy annuals? Or, will they bloom into early summer?

Yep! Most hardy annuals (like feverfew, larkspur, nigella) bloom late spring into early summer, then fade once the heat kicks in. That’s perfect timing—you can pull them and replant with your zinnias, cosmos, celosia, or dahlias. So yes, same beds work fine, just rotate them out when they’re done.