Every year, it sneaks up on us—the first bees of spring. One day the garden still looks half-frozen, and the next, a few fuzzy little foragers are already out, zigzagging through the gray, looking for breakfast. The problem? There’s nothing to eat.

Most gardeners don’t realize how early native bees wake up. Mason bees, mining bees, and bumblebee queens start flying weeks before most flowers bloom. Scientists call this the “spring hunger gap,” and it’s one of the biggest reasons early pollinators struggle to survive.

But you can fix that before winter even begins. Fall is your window. It’s when nature plants her wildflowers—when seeds hit the soil, freeze, thaw, and wake up strong in spring. You can mimic that same rhythm just by scattering a few native seeds this month and letting the weather do the work.

By the time those first bees crawl out in March, your garden will already be blooming—an all-you-can-eat buffet of nectar and pollen that could literally save their season.

Here are 10 native, nectar-rich wildflowers to plant before the month ends—that will feed the first bees of spring—and bring your garden to life before anyone else’s has even started.

Why It’s Important to Plant Early-Flowering Natives

Here’s the gardening myth almost everyone believes: “Bees show up when the flowers bloom.”

Sounds right, doesn’t it? Except it’s completely backward. Bees don’t follow the flowers—flowers follow the bees.

And that’s where things are falling apart. By the time most gardens burst into color, the damage is already done. Over 70% of native bee species wake weeks before the first tulips bloom—hungry, cold, and desperate. Scientists call it the “spring hunger gap”—a perilous few weeks when bees emerge but flowers haven’t yet caught up. A 2024 Oxford study found that just two nectarless weeks can kill up to 87% of queen bumblebees before they ever start a colony. When early blossoms are available, survival shoots to nearly 100%—a tiny difference in timing that determines the fate of an entire generation.

Modern gardens often miss that window. Research from the University of Bristol showed that while gardens provide only about 15% of annual nectar, they supply up to 90% during early spring—but only if native plants are present. In landscapes stripped of early natives, bees wake into what ecologists call a “floral desert,” burning through their last reserves as they search for food that isn’t there.

Even small patches of early-flowering natives make a measurable difference. The U.S. Forest Service found that early-blooming shrubs make up less than 10% of total flowers yet draw over half of all bee visits in spring. Another British Ecological Society study confirmed that early native forbs directly boost bumblebee abundance and colony success.

1. Prairie Violet (Viola pedatifida)

If you’ve ever walked a prairie in early spring, you’ve probably spotted these little sparks of purple peeking through the brown grass before anything else dares to bloom. Prairie violets are some of the first native flowers to wake up, and that’s exactly what makes them so valuable—you’ll have color in the garden before most perennials even think about it, and the first bees of the season will thank you for it.

October is the perfect time to sow them. In the wild, their seeds fall in late summer and spend the winter sleeping under snow, soaking up cold and moisture. You can do the same at home by sprinkling seed over bare soil and letting nature handle the rest. Don’t overthink it—these little plants evolved to germinate through frost, thaw, and spring rain.

By March or April, you’ll see small, lacy leaves followed by those bright violet-blue flowers. Early native bees—especially small mining bees—flock to them, and fritillary butterflies use them as host plants. They’re small but mighty, and once you plant them, they’ll quietly return year after year without taking over.

Zones: 3–8

Size: 4–8 inches tall × 6–10 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun to light shade; lean, well-drained soil; fall sowing is best; drought-tolerant once established; self-sows lightly but stays polite.

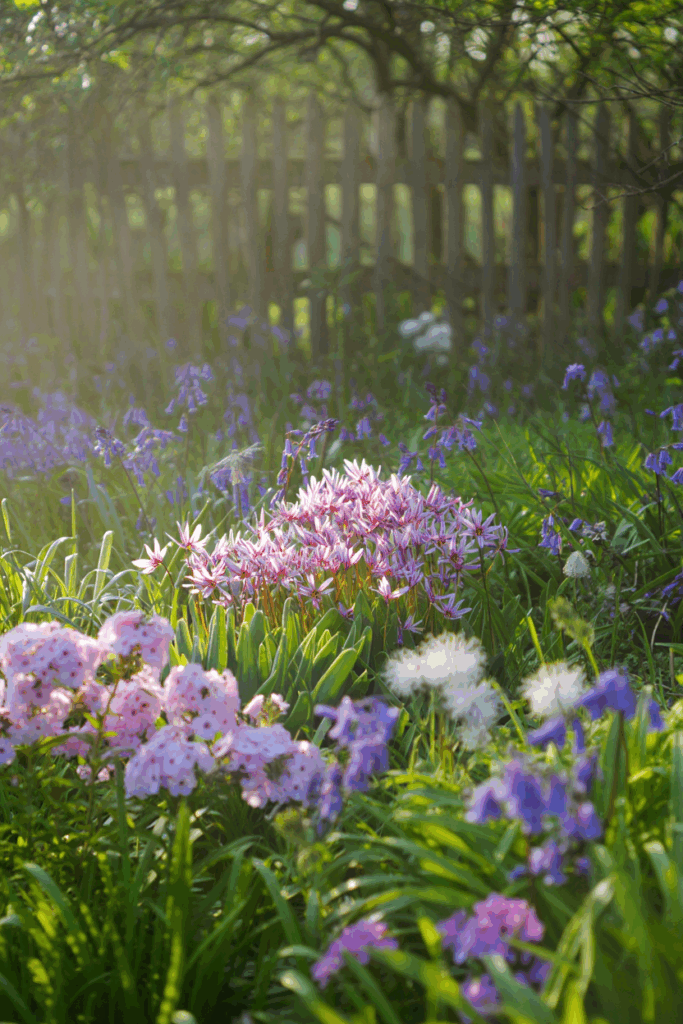

2. Eastern Blue Phlox (Phlox divaricata)

If you want a garden that hums with life the moment spring arrives, don’t skip Eastern blue phlox. Its fragrant, sky-colored blooms appear right when bees and butterflies are desperate for nectar—and before most other flowers even show a hint of green. The soft, sprawling plants weave naturally through woodland edges or shady borders, adding that dreamy, old-fashioned spring charm every cottage garden needs.

October is the perfect time to sow it. In nature, blue phlox seeds fall in late summer and rest all winter under leaves and snow. That cold period helps them germinate strong when spring warmth returns. You can mimic that cycle by sowing directly into moist, well-drained soil in fall and letting nature handle the chill. By March or April, you’ll see tidy mounds of green foliage followed by a cloud of delicate blue blossoms.

Early solitary bees, bumblebee queens, and even butterflies like the spring azure rely on this nectar source before most perennials bloom. It’s one of the easiest ways to turn a shady corner into a pollinator haven.

Zones: 3–8

Size: 8–12 inches tall × 12–18 inches wide

Care requirements: Part to full shade; rich, moist, well-drained soil; sow in fall for natural cold stratification; cut back lightly after bloom to encourage fuller growth; spreads politely by seed and short runners.

3. Lanceleaf Tickseed (Coreopsis lanceolata)

There’s something cheerful about a clump of lanceleaf coreopsis in bloom. Those golden-yellow daisies look like they’re catching sunlight and throwing it right back, brightening up any space they grow in. They’re tough, native, and one of the easiest ways to keep your garden buzzing with life.

If you sow the seeds in October, you’re doing exactly what nature does. Coreopsis seeds fall to the ground in late summer and spend the winter resting in cold soil. That chill helps them sprout stronger when spring warms up. Just scatter the seed over bare, well-drained soil, press it in lightly, and forget about it until spring. The first flush of flowers will be waiting for you before you know it.

Once established, lanceleaf coreopsis doesn’t need much. It thrives in dry, sandy soil, shrugs off heat, and blooms for weeks with almost no care. Bees love it, butterflies love it, and you’ll love how it brings effortless color to your garden year after year.

Zones: 4–9

Size: 12–24 inches tall × 12–18 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun; average to dry soil; sow in fall for natural stratification; drought-tolerant and low-maintenance; attracts a wide range of pollinators.

4. Jacob’s Ladder (Polemonium reptans)

There’s something quietly magical about Jacob’s ladder. Long before most perennials wake up, its fresh green foliage unfolds like tiny rungs of a ladder, followed by clusters of soft lavender-blue bells that nod in the spring breeze. It’s one of those plants that looks delicate but shrugs off cold nights and unpredictable spring weather without complaint.

If you’ve ever wanted an easy way to bring color into shady spots early in the season, this is it. October is the perfect time to sow Jacob’s ladder from seed. Just sprinkle the seeds over moist soil and let winter do its thing—the natural chill helps them germinate strong and even. By the time the first bees start flying, you’ll already have a patch in bloom, feeding hungry pollinators that have been waiting all winter for something to sip.

Jacob’s ladder fits beautifully under trees, along woodland edges, or tucked beside spring bulbs where the light is soft. It won’t take over or sprawl, and once it’s happy, it’ll quietly self-sow enough to keep the display going year after year.

Zones: 3–8

Size: 12–18 inches tall × 12–18 inches wide

Care requirements: Part shade; rich, moist, well-drained soil; fall sowing for best results; low-maintenance, deer-resistant, and one of the earliest reliable nectar sources for spring bees.

5. Shooting Star (Dodecatheon meadia)

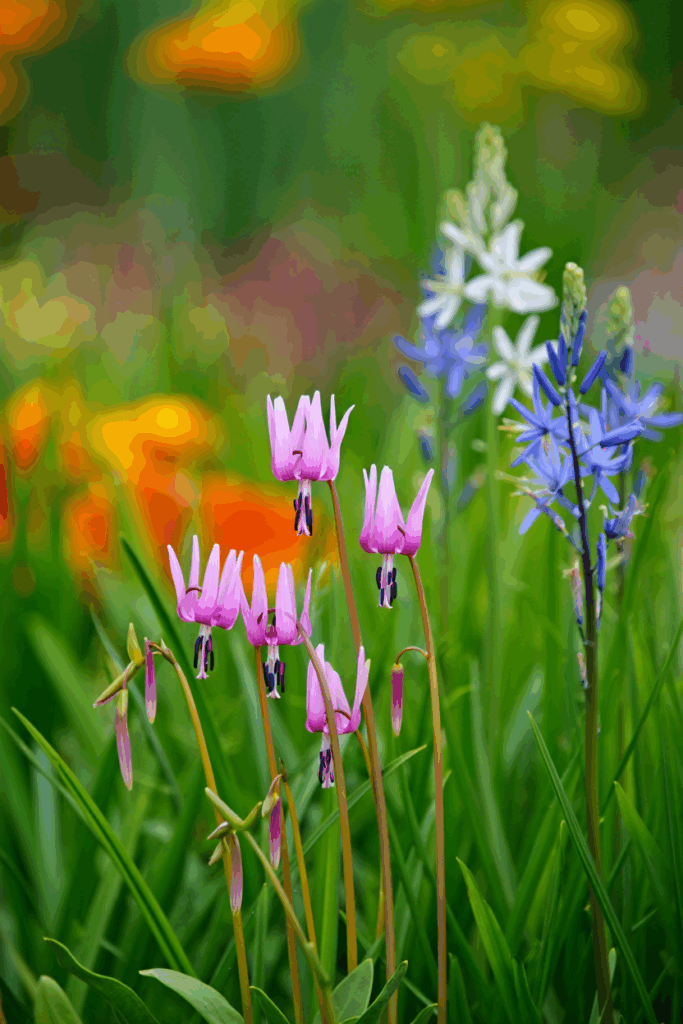

If there’s one wildflower that feels straight out of a fairytale, it’s the shooting star. Each bloom looks like it’s caught mid-flight—petals swept backward like tiny pink comets just above the foliage. They appear in those quiet, early weeks of spring when bees are first waking up, and their unusual shape is more than just pretty—it’s perfectly designed for buzz pollination. You’ll actually see bumblebees cling to the flower and vibrate their flight muscles to shake the pollen loose.

Shooting stars are best started in fall because their seeds need winter’s chill to germinate. In nature, they fall to the ground in late summer, get buried in leaf litter, and spend months under cold, damp conditions before sprouting with the spring thaw. To mimic that, scatter seeds over moist, well-drained soil in October, press them in gently, and let nature handle the rest. Don’t be surprised if they take a year or two to bloom—they’re slow to start, but worth every bit of patience.

Once established, shooting stars naturalize beautifully in part shade or open woodland gardens. They’ll bloom gloriously in April and then go dormant by summer, quietly resting underground until next year’s show.

Zones: 4–8

Size: 8–16 inches tall × 6–12 inches wide

Care requirements: Part shade; moist, well-drained soil; fall sowing or cold stratification required; allow foliage to die back naturally after bloom; long-lived and beloved by early bumblebees.

6. Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis)

If you want a plant that’s as tough as it is beautiful, wild lupine deserves a spot in your garden. Those deep blue flower spikes show up just as the first bumblebees are buzzing again, and they’re a magnet for early pollinators. Even better, this native lupine is the one and only host plant for the endangered Karner blue butterfly—so every seed you sow truly makes a difference.

October is the perfect time to get them started. In the wild, lupine seeds fall to the ground and spend the winter under snow before sprouting in spring. You can mimic that by sowing directly in sandy, well-drained soil now and letting the cold weather do the work. Once the roots are down, these plants handle drought, poor soil, and full sun like champions.

Wild lupine doesn’t need pampering—just space, sunshine, and a little patience. Within a year or two, you’ll have sturdy plants that bloom reliably every spring and gently reseed themselves without ever becoming a nuisance.

Zones: 3–8

Size: 12–24 inches tall × 12–18 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun; dry, sandy, or gravelly soil; sow in fall for natural cold stratification; drought-tolerant; attracts early bees and butterflies.

7. Blue-Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium)

Don’t let the name fool you—blue-eyed grass isn’t a grass at all. It’s a tiny member of the iris family, and when it blooms, those starry violet-blue flowers with golden centers light up the garden like little sparks. It’s one of the earliest natives to flower in spring, just in time to feed the first small bees and pollinators searching for nectar after winter.

October is the perfect month to sow it. In the wild, blue-eyed grass drops its seeds in late summer, and they rest through the cold months until spring warmth wakes them up. You can easily mimic that by sprinkling seeds over moist soil and letting nature take care of the chill. By April, you’ll see neat clumps of slender, grass-like leaves topped with cheerful blooms that open in the morning and close by afternoon.

This is a great choice for naturalized lawns, sunny borders, or along paths where you want something delicate but dependable. Once established, it handles drought, poor soil, and neglect with ease—proof that beauty and toughness can go hand in hand.

Zones: 3–9

Size: 6–12 inches tall × 6–12 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun to part shade; moist to average, well-drained soil; fall sowing for best germination; tolerates drought once established; great for early bees.

8. Golden Alexanders (Zizia aurea)

When most of the garden is still stretching awake, Golden Alexanders are already busy feeding bees. Those bright, umbrella-like clusters of yellow flowers show up just as spring shifts into gear, giving pollinators an early reason to visit your garden. It’s one of those dependable natives that never asks for much but quietly makes everything feel more alive.

Fall is the best time to sow the seeds. In nature, they drop to the soil in late summer and wait out the cold months before sprouting with spring warmth. You can do the same—just scatter the seed in October, press it lightly into the soil, and walk away. By May, you’ll have golden blooms that bridge the gap between tulips and summer perennials.

Golden Alexanders are also a host plant for black swallowtail butterflies, which means you’re not just feeding bees—you’re growing a nursery for the next generation of butterflies too.

Zones: 3–9

Size: 18–30 inches tall × 12–18 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun to part shade; moist to average soil; sow in fall for natural stratification; easy, adaptable, and pollinator-approved.

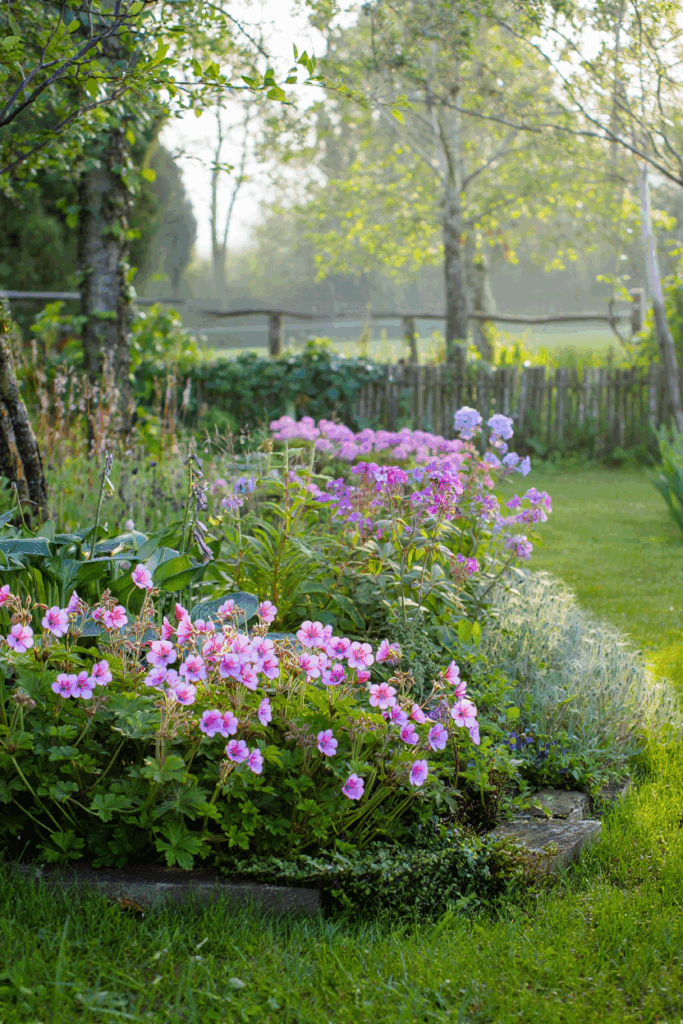

9. Wild Geranium (Geranium maculatum)

If your shade garden feels a little dull in spring, wild geranium is your fix. Its soft pink blooms appear just as the trees leaf out, filling those in-between weeks with color and movement. Every morning, you’ll find bees tucked inside the open flowers, gathering nectar before the heat of the day sets in. It’s one of those steady, dependable natives that quietly supports pollinators without needing much attention from you.

Fall is the easiest time to start it. In the wild, geranium seeds fall in late summer, lie dormant all winter, and sprout when the soil warms in spring. You can mimic that by sowing in October—just scatter the seeds where you want them, press them into the soil, and let nature take care of the rest. Once they establish, they’ll come back every year, slowly forming pretty drifts of green leaves and soft flowers.

Wild geraniums blend beautifully with ferns, woodland phlox, or columbine and give your shade beds that relaxed, natural look we all love.

Zones: 3–8

Size: 12–18 inches tall × 12–24 inches wide

Care requirements: Part shade; moist, well-drained soil; fall sowing for natural cold stratification; easy, reliable, and great for early bees.

10. Blue-Eyed Mary (Collinsia verna)

If you want a native that actually shows up when bees need it most, forget the fancy hybrids and start here. Blue-eyed Mary doesn’t wait for warm weather or perfect conditions—it gets up early, blooms fast, and feeds bees while the rest of the garden’s still hitting snooze.

Those tiny two-tone flowers—blue on top, white underneath—aren’t just pretty; they’re purpose-built for small native bees and hoverflies. While your tulips are still thinking about it, these blooms are already open for business, pumping nectar into the ecosystem when it’s in short supply.

Native from the Midwest to the Appalachians, this plant thrives on almost no effort. Scatter the seed in fall, walk away, and let the cold do the work. Come March, it germinates, grows, blooms, and reseeds before summer even starts. No fertilizer, no fuss, just results.

Blue-eyed Mary is proof that early pollinator support doesn’t have to be complicated—it just has to be timed right.

Zones: 4–8

Height/Spread: 6–12 in. × 6–10 in.

Conditions: Part shade; moist to average soil; sow in fall for natural stratification; a vital early food source for solitary bees.

11. Pasque Flower (Pulsatilla patens)

If any native flower captures the spirit of resilience, it’s the pasque flower. It blooms so early—sometimes through melting snow—that it almost feels impossible. Those silky purple blossoms with golden centers are a beacon for the first bees of spring, offering nectar when little else exists.

Native to prairies and open woodlands, this perennial thrives in cold climates and poor, well-drained soil. Its fuzzy stems and leaves protect it from frost, allowing it to flower long before other perennials dare to try. Bumblebee queens, small mining bees, and early hoverflies are frequent visitors, taking advantage of one of the earliest open blooms in the season.

Sow the seeds in fall; they need a good freeze to break dormancy. Once established, pasque flowers form compact clumps that return every year, spreading slowly and blooming reliably—often before the snowdrops fade.

Zones: 4–7

Size: 6–12 inches tall × 8–12 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun; sandy, well-drained soil; fall sowing for natural cold stratification; drought-tolerant once mature; among the earliest sources of nectar for spring bees.

12. Prairie Smoke (Geum triflorum)

Prairie smoke looks like something out of a dream—and it blooms when the world still feels half asleep. In late April or early May, its dusky pink nodding flowers rise from ferny foliage, feeding mining bees and early bumblebees that need every calorie they can find. Then the real show begins: the seed heads unfurl into wispy, silver-pink plumes that shimmer like smoke in the morning light.

This is a tough, long-lived native that thrives in poor, well-drained soil and full sun. It’s perfect for rocky spots, dry borders, or prairie-style gardens where you want texture and motion without fuss.

Fall sowing is key—its seeds need months of cold to germinate. Plant in October, and by next spring you’ll see its fine leaves pushing through the soil, ready to bloom as soon as the bees do.

Zones: 3–7

Size: 6–12 inches tall × 12 inches wide

Care requirements: Full sun; dry to average, well-drained soil; drought-tolerant once established; fall sowing for natural stratification; beloved by early bees and butterflies.

Written By

Amber Noyes

Amber Noyes was born and raised in a suburban California town, San Mateo. She holds a master’s degree in horticulture from the University of California as well as a BS in Biology from the University of San Francisco. With experience working on an organic farm, water conservation research, farmers’ markets, and plant nursery, she understands what makes plants thrive and how we can better understand the connection between microclimate and plant health. When she’s not on the land, Amber loves informing people of new ideas/things related to gardening, especially organic gardening, houseplants, and growing plants in a small space.