By the time September light softens and the hum of summer fades, most gardens start to look a little tired. The zinnias are spent, the coneflowers are turning to seed, and we tell ourselves it’s time to wind things down. But in the quiet, something small is still moving — a bumblebee tracing the last open blossoms, a monarch drifting low, searching for one final sip.

For pollinators, fall isn’t a time to rest. It’s the final, frantic push before winter — the difference between survival and collapse. And research shows just how high the stakes are: according to a 2024 Royal Society study, nectar availability in most gardens drops by over 75% between August and October. By late fall, well-planted gardens may provide up to 93% of the remaining nectar across the landscape — the only lifeline for bees and butterflies when fields and roadsides have gone bare.

That means what’s blooming in your garden right now matters more than ever. The Xerces Society has named fall-blooming native plants among the top priorities for sustaining pollinators in North America — and for good reason. These species close the “nectar gap,” offering both energy and shelter when the rest of the landscape has gone quiet.

So before you hang up your pruners for the season, give your garden one last gift — and one that truly gives back. Here are 10 nectar-rich native fall flowers that keep the color, movement, and life going long after summer’s bloom has passed.

1. Sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale)

Just when your garden starts looking tired in late August, sneezeweed wakes it back up. Those sunny, button-centered blooms can carry a border straight through October, glowing in warm shades of gold, amber, and rust. It’s one of those plants that quietly holds the season together when everything else gives up.

Don’t let the name fool you — sneezeweed won’t trigger allergies. Its pollen sticks to the bodies of bees, butterflies, and hoverflies, not the wind. In fact, it’s a late-season lifeline for pollinators stocking up before frost, especially migrating monarchs.

Native to North American wetlands and open meadows, sneezeweed is tougher than it looks. It’s hardy in Zones 3–8, loves full sun, and can handle average garden soil as long as it doesn’t bake dry. At 3–5 feet tall, it stands proudly without flopping and mixes easily with asters, goldenrods, and native grasses for a rich fall tapestry. If you want your garden to stay alive and buzzing after summer fades, this is one to plant once and enjoy for years.

2. Blue-Stem Goldenrod (Solidago caesia)

If you think all goldenrods are rough, roadside weeds, this one will change your mind. Blue-stem goldenrod is a gentle woodland native that brings a soft glow to shady or half-sunny gardens just when you need it most — from late August right into October. Instead of towering over everything, it forms graceful, arching stems (about 2–3 feet tall) dusted with tiny golden blooms that hug the stems like fireflies caught in flight.

It’s native across much of eastern North America and thrives in Zones 4–8, preferring part shade and well-drained, humus-rich soil. Unlike the aggressive field types, this species stays well-behaved and even elegant — perfect for tucking under trees or along woodland paths.

And while it looks delicate, it’s a serious pollinator favorite. The slender clusters hum with native bees, hoverflies, and small butterflies, providing nectar deep into fall when few other flowers remain. Even migrating monarchs and late-season skippers pause here for a sip. If you’ve ever wished for a goldenrod that feels at home in a shady, natural-style garden, this is the one that keeps the light — and the life — going long after summer fades.

3. Downy Skullcap (Scutellaria incana)

Here’s a native that proves fall color doesn’t have to mean gold or orange. Downy skullcap sends up soft, silvery stems topped with cool blue-violet blooms that carry the spirit of summer right into September and October. Each flower looks like a tiny snapdragon, and together they form airy wands that sway above the foliage — subtle, calm, and quietly striking in late-season light.

Native to open woods and prairies across the eastern and central U.S., it’s hardy in Zones 4–8 and thrives in full sun to light shade. Once established, it’s drought-tolerant and content in average, well-drained soil — no fuss, no constant watering. The “downy” part of its name refers to the soft hairs on its stems and leaves, which help it hold moisture and deter deer.

But what really makes this plant special is its pollinator pull. Those tubular flowers are a magnet for bumblebees, long-tongued native bees, and small butterflies, all desperate for late nectar. As the rest of the border starts to fade, skullcap keeps working quietly in the background — feeding pollinators, holding its shape, and adding that rare, calming blue to the fall palette.

4. White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima)

If you’ve ever walked through the woods in early fall and noticed a soft white shimmer under the trees, chances are it was white snakeroot. This native wildflower lights up shady edges and woodland paths from late August through October, just when the forest starts to dim. Its fluffy white clusters float above deep green leaves, catching the low autumn light like mist.

Native across eastern and central North America, it’s hardy in Zones 3–8 and thrives in part shade to full shade — one of the few late bloomers that doesn’t need sun to shine. It spreads gently by rhizomes, forming easy drifts that look natural but not weedy if you give them a bit of space.

White snakeroot is a quiet powerhouse for late-season pollinators. Its nectar draws in small native bees, wasps, and moths, providing steady forage when most woodland flowers are gone. Deer tend to ignore it, and once it settles in, it can handle drought surprisingly well for a shade plant.

It has a fascinating history too — once notorious for causing “milk sickness” when cattle grazed on it — but in today’s gardens, it’s all about balance and beauty. If your late garden needs a little brightness beneath the trees, white snakeroot brings that calm, moonlit glow just when you thought the show was over.

5. New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis)

When everything else starts fading to beige, New York ironweed shows up like the exclamation point of late summer. Its rich purple-violet flower clusters tower over the border — bold, upright, and buzzing with life from August through October. There’s nothing shy about this native; it brings real drama to the fall garden, especially against golden grasses or yellow goldenrod.

Native to moist meadows and stream edges across the eastern U.S., it’s hardy in Zones 5–9 and loves full sun with decent moisture. At 4–7 feet tall, it makes a natural backdrop or living screen, and those sturdy stems really live up to the name “ironweed.” They don’t flop, even in storms, and they hold their color beautifully right up until frost.

But the real show is the pollinator traffic. Ironweed’s nectar-rich blooms are a magnet for monarchs, swallowtails, fritillaries, and native long-tongued bees. On warm September days, it can look like the whole plant is moving from all the wings visiting it. And when the flowers fade, the seedheads stay decorative — catching the light and feeding finches well into winter.

If your garden feels dull after the coneflowers quit, plant ironweed once and let it remind you how alive late summer can still feel.

6. Showy Goldenrod (Solidago speciosa)

Every fall garden needs a plant that refuses to fade quietly — and Showy goldenrod does exactly that. While most flowers are winding down, its upright golden spires blaze into bloom from late August through October, catching every drop of autumn light. The color is pure, clear gold — the kind that turns a whole border warm even on a chilly day.

Native to prairies and open woodlands across eastern and central North America, it’s hardy in Zones 3–8 and thrives in full sun with average to dry soil. Unlike some goldenrods, this one stays neatly clumped and doesn’t run — making it perfect for borders, meadow edges, or cottage-style plantings. It’s tough, drought-tolerant, and deer-resistant, yet refined enough to mix with asters, little bluestem, or blazing star for a natural but polished look.

And it’s not just beautiful — it’s busy. The blooms pulse with native bees, beetles, and migrating butterflies, all drawn to its late-season nectar.

7. Aromatic Aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium)

When you think the season’s over, Aromatic aster proves the garden still has one last show left. In September and October, its mounds of lavender-blue daisies open all at once, turning the plant into a cushion of color that lasts until hard frost. Brush against the foliage and you’ll catch its fresh, resinous scent — a bonus that gives the plant its name.

Native from the Midwest to the eastern U.S., this aster thrives in Zones 4–8 and loves full sun and well-drained soil. It stays compact — usually 1–2 feet tall — so it never flops like taller asters do. Once established, it’s tough, drought-tolerant, and deer-resistant, thriving even in dry, rocky spots or poor clay. It’s the kind of plant you forget about all summer — until suddenly it’s glowing purple while everything else is fading brown.

Pollinators love it as much as gardeners do. Its late blooms feed native solitary bees, bumblebees, and migrating monarchs, providing crucial nectar right before winter. Pair it with showy goldenrod or little bluestem and you’ll have one of the most reliable — and breathtaking — fall combinations around.

8. Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata)

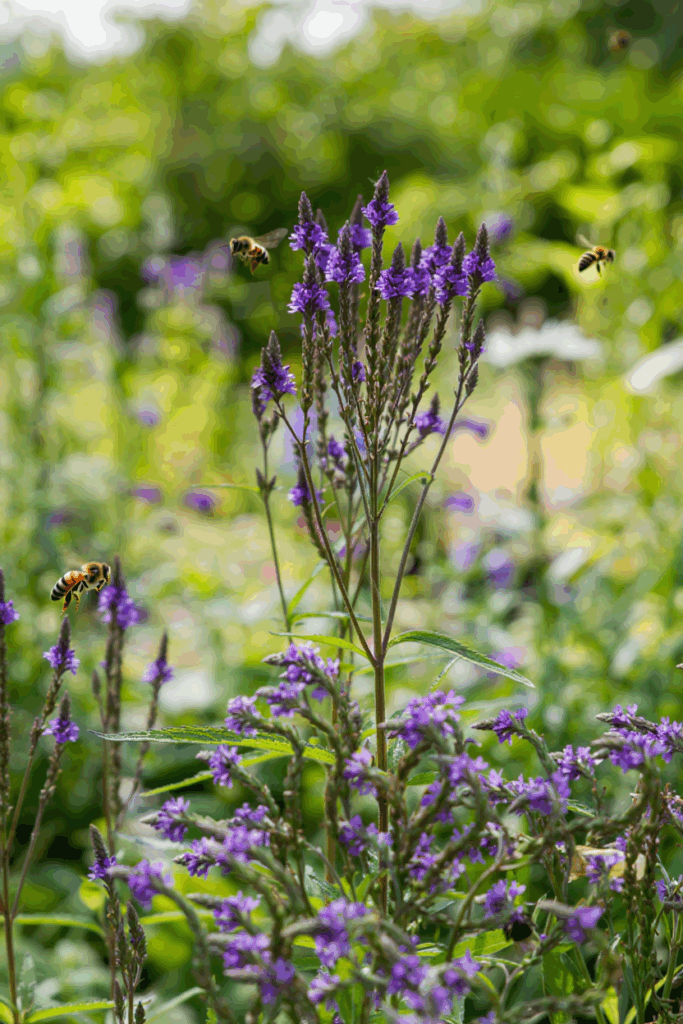

When the midsummer fireworks fade, Blue vervain steps in to keep the garden buzzing right through early fall. Its slender spikes of violet-blue flowers rise like candelabras above the foliage, opening a few tiny blooms at a time from late July through September — sometimes even into October if the weather stays warm. It’s a graceful, upright native that adds vertical texture and movement wherever it grows.

Native to wet meadows, ditches, and prairies across nearly all of North America, Blue vervain is hardy in Zones 3–8. It loves full sun and moist soil, but it’s surprisingly adaptable — happy in average garden beds as long as it doesn’t dry out completely. The plants grow 3–5 feet tall, forming slim vertical accents that blend beautifully with Joe Pye weed, swamp milkweed, and sneezeweed.

Ecologically, it’s a powerhouse. The nectar-rich blooms attract monarchs, swallowtails, skippers, and native bees, while goldfinches feast on the seeds in late fall. Its long bloom time bridges the gap between summer perennials and true fall wildflowers, keeping your pollinator corridor active when few others do.

If you love that wild-meadow energy but want something elegant and purposeful, Blue vervain brings both — soft color, steady bloom, and a hum of life that carries your garden gracefully toward autumn.

9. Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

When almost everything else in the garden starts to fade, Cardinal flower steals the spotlight. Its brilliant red blooms blaze from August into early October, calling in hummingbirds like a neon sign. Few native flowers match its intensity — it brings life, color, and motion back to the garden just when things are starting to slow down.

This North American native is hardy in Zones 3–9 and thrives in moist, rich soil with full sun or part shade. In the wild, you’ll find it along streambanks and wet meadows, but it adapts beautifully to rain gardens or consistently watered borders. Standing 2–4 feet tall, its strong, vertical stems create a natural focal point among ferns, Joe Pye weed, or blue lobelia.

Ecologically, it’s one of the best late-season nectar sources for hummingbirds, butterflies, and native long-tongued bees. The tubular flowers are built perfectly for hummingbirds, whose slender beaks pollinate them as they feed. Deer rarely touch it, and once it’s happy, it may reseed lightly to form small, glowing colonies.

If your garden ever feels like it runs out of energy after midsummer, plant cardinal flower — it’ll keep the buzz (and the beauty) going right through the first frost.

10. New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

Just when the garden starts to fade, New England aster takes over like a burst of purple fireworks. From late August right through October, its violet-blue flowers open by the hundreds, each one a landing pad for butterflies and bees desperate for that last taste of nectar. Few plants bring this much life back into the garden when most colors are slipping away.

Native across most of the eastern and central U.S., it’s hardy in Zones 3–8 and thrives in full sun and average to moist soil. Give it room — it can grow 3 to 6 feet tall — or pinch the stems in early summer for a bushier shape. The show is worth it: every stem becomes a pillar of blooms that glows in low autumn light.

Pollinators absolutely swarm it. Monarchs, painted ladies, bumblebees, sweat bees, and hoverflies all rely on its nectar to fuel migration or overwintering. When paired with goldenrod or Joe Pye weed, it creates a fall border that hums with energy and feels alive until the very last frost.

If your garden ever feels empty after summer, plant New England aster — it’s the flower that keeps the season going long after you thought it was over.

Written By

Amber Noyes

Amber Noyes was born and raised in a suburban California town, San Mateo. She holds a master’s degree in horticulture from the University of California as well as a BS in Biology from the University of San Francisco. With experience working on an organic farm, water conservation research, farmers’ markets, and plant nursery, she understands what makes plants thrive and how we can better understand the connection between microclimate and plant health. When she’s not on the land, Amber loves informing people of new ideas/things related to gardening, especially organic gardening, houseplants, and growing plants in a small space.