You know that feeling when you finally find a plant the deer won’t destroy — and then it ends up taking over your garden instead? Yeah… been there.

For years, I thought “deer-resistant” meant “problem solved.” I wanted perennials that could survive on their own — low-maintenance, reliable, and unbothered by browsing. And for a while, they were. Until they weren’t.

That tidy clump of minty nepeta? It turned into a fuzzy carpet that swallowed the path. The patch of obedient plant? Anything but obedient. One season they’re filling gaps; the next, they’re creeping under fences, crowding out natives, and popping up where you never planted them.

Here’s the irony — the same traits that make these plants unappealing to deer (strong scent, bitter sap, or mild toxicity) also make them tenacious survivors. They don’t just withstand browsing — they thrive, spread, and stake their claim wherever they can. Before you know it, you’ve traded one problem (deer) for another (plants you can’t control).

Not every “deer-resistant” perennial misbehaves, of course. Some stay perfectly polite in the right conditions. But after years of trial, error, and too many weekends pulling runners out of the soil, I’ve learned which ones to skip.

So before you fall for another “deer-resistant” darling, here are ten that have worn out their welcome — and the native alternatives that bring the same beauty without the chaos.

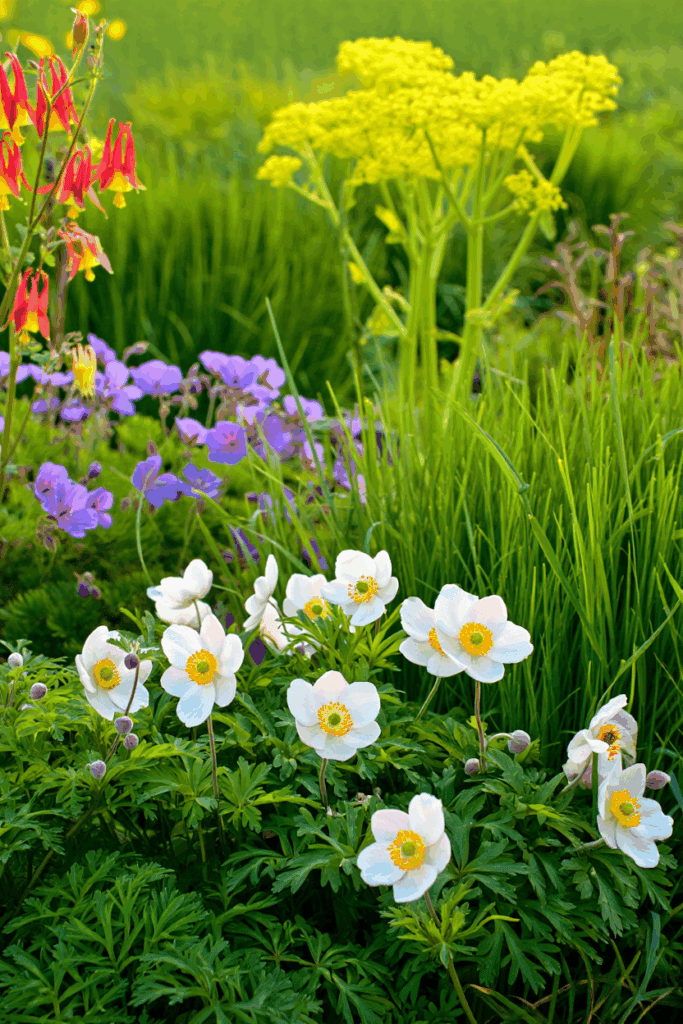

1. Japanese Anemone (Anemone × hybrida)

It’s easy to fall for Japanese anemones. Those soft pink and white blooms floating above deep green foliage in late summer feel like the definition of garden grace. They’re tough, deer rarely touch them, and they seem to bloom forever when most plants are calling it quits.

But here’s what many gardeners learn the hard way — once Japanese anemones feel at home, they don’t stay put. Their roots form tough, wiry rhizomes that spread underground and pop up everywhere: between pavers, inside shrubs, even in your lawn. The first year or two they look polite, then suddenly they’re running under fences and choking neighboring perennials. Cutting or dividing them usually makes it worse, since every small root piece can grow back. In rich soil or regular moisture, they’ll take over before you know it.

A Better Alternative: Aromatic Aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium).

If you love that late-season color and soft, natural shape, aromatic aster gives you everything good about Japanese anemones without the invasive habit. It’s a native perennial that blooms from late summer into fall, covered in lavender-blue daisy flowers that butterflies and native bees depend on. Deer tend to leave it alone, and it stays neatly in place — no underground runners, no surprise seedlings. It’s also tougher than it looks, handling heat, drought, and poor soil with ease.

2. Obedient Plant (Physostegia virginiana)

The name “obedient plant” sounds charming — and at first, it lives up to it. Those snapdragon-like pink or white spikes stand tall and tidy in late summer, and if you push one bloom sideways, it politely stays where you put it (hence the name). It’s native to North America, deer usually ignore it, and it fills that midsummer color gap beautifully.

But here’s the catch: obedient plant isn’t nearly as obedient as it sounds. Once it’s happy, it spreads fast by underground rhizomes, sending up new shoots all over the bed. In rich or consistently moist soil, it can quickly form a dense colony that crowds out slower-growing perennials. Digging or dividing it just seems to make more of it — and before long, you’re chasing runners across your garden every spring.

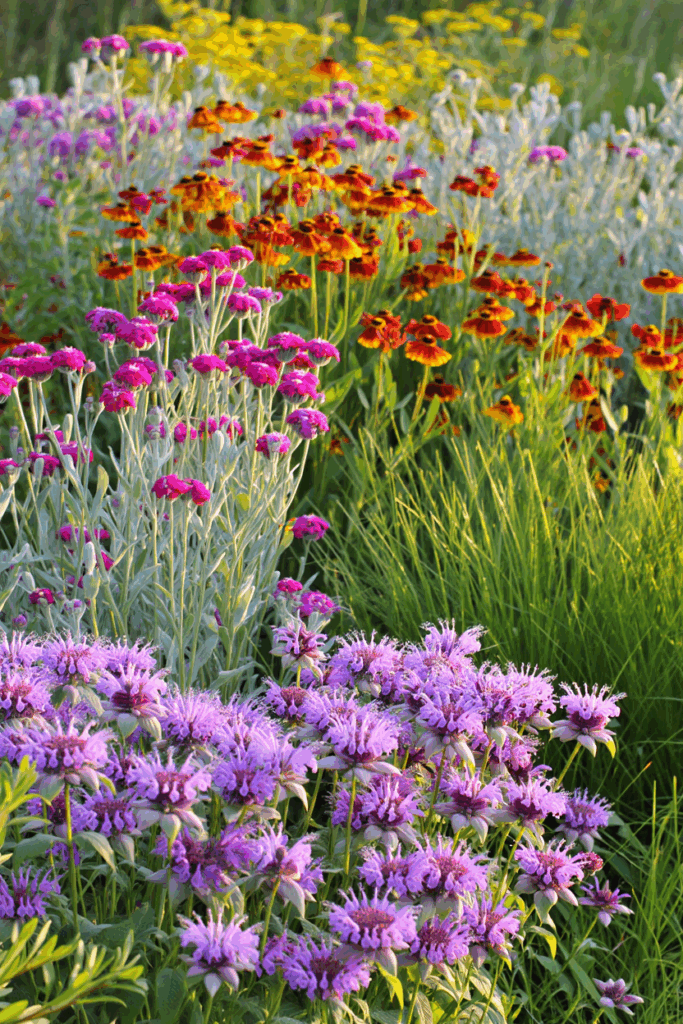

A Better Alternative: Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa).

If you’re after the same upright form and bee-magnet blooms, wild bergamot delivers — and behaves. This native monarda has clusters of lavender-pink flowers that attract hummingbirds, bumblebees, and butterflies, but it expands gently instead of taking over. It’s drought-tolerant, deer-resistant, and thrives in full sun with average soil. You’ll still get that bold, cottage-garden color — just in a plant that respects its neighbors.

3. Russian Sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia)

Russian sage has earned a reputation as a “can’t-fail” perennial — and it’s easy to see why. Those silvery stems, ferny leaves, and clouds of lavender-blue flowers can turn any dry, sunny corner into something magical. It laughs at drought, shrugs off deer, and blooms for months when most plants are fading. For years, it’s been the go-to plant for low-water borders and pollinator gardens.

But lately, Russian sage has started showing up where it doesn’t belong — escaping from gardens and establishing in wild areas, roadsides, and prairie edges. The problem is its seed. Each flower produces hundreds of tiny, wind-dispersed seeds that germinate easily in bare or disturbed soil. Over time, it can form loose colonies that crowd out native grasses and wildflowers, especially in arid western states. Add to that its woody base and deep roots, and you’ve got a plant that’s tough to pull once it settles in.

A Better Alternative: Prairie Sage (Artemisia ludoviciana).

If you love that silvery foliage and deer resistance, Artemisia ludoviciana offers nearly the same texture and color — but it’s native, better behaved, and ecologically valuable. Its aromatic leaves deter deer just as effectively, and it thrives in the same poor, well-drained soils that Russian sage prefers. In late summer, its pale silver-gray foliage shimmers under sunlight, adding the same haze and movement to the garden.

4. Lamb’s Ear (Stachys byzantina)

There’s something irresistible about lamb’s ear. Those velvety, silver leaves look like they were made for cottage gardens — soft, tidy, and nearly indestructible. They thrive in poor soil, laugh at drought, and deer won’t touch them. For a few seasons, they seem like the perfect low-maintenance filler.

But once they settle in, lamb’s ear starts to sprawl. It spreads by creeping stems that root wherever they land, slowly forming a thick mat that crowds out other plants. In humid regions, it’s prone to rot and mildew; in dry ones, it runs wild through borders and gravel paths. Either way, it becomes more work than it’s worth. And those seedheads? They scatter themselves just enough to pop up where you don’t want them next year.

A Better Alternative: Texas Betony (Stachys coccinea).

If you love that fuzzy texture but want something with real ecological value, try Texas betony — a North American native from the same genus. Its foliage has that same soft, tactile quality, but instead of silver mats, it forms neat, upright mounds topped with vivid red tubular flowers from spring through fall. Pollinators can’t resist it — hummingbirds, native bees, and butterflies all flock to its blooms. It’s drought-tolerant, deer-resistant, and much better behaved in mixed plantings.

5. Lilyturf (Liriope spicata)

Lilyturf — or Liriope spicata — is one of those plants that seems to solve every problem. It’s evergreen, deer-resistant, thrives in shade or sun, and fills bare spots fast. Many gardeners use it as a tidy border or lawn substitute because it’s tough and needs almost no attention. For a few years, it behaves beautifully — a perfect edging of glossy, grass-like leaves and little lavender flower spikes.

Then one day, you realize it’s everywhere. Lilyturf spreads by underground rhizomes, forming dense mats that creep through mulch, under fences, and straight into the lawn. Once it’s established, good luck removing it — even small root fragments re-sprout, and the thick tangle of roots can choke out native groundcovers. In much of the Southeast and mid-Atlantic, it’s now invading forest edges and stream banks, where it smothers native sedges and woodland wildflowers.

A Better Alternative: Pennsylvania Sedge (Carex pensylvanica).

If you love that soft, tufted look but want something truly eco-friendly, Pennsylvania sedge is the answer. It’s a native, deer-resistant sedge that forms graceful clumps of fine, arching blades, spreading gently by rhizomes without becoming aggressive. It thrives in dry shade, partial sun, or under trees — all the same tough spots where lilyturf usually goes — but it stays in bounds and supports native insects.

6. Creeping Bellflower (Campanula rapunculoides)

Creeping bellflower looks innocent enough at first — graceful lavender bells that nod in early summer, blooming for weeks even in poor soil. It’s hardy, drought-tolerant, and deer usually ignore it. For many gardeners, that combo sounds perfect. But C. rapunculoides is one of those plants that quickly turns from “pretty” to “permanent.”

It spreads two ways — by deep, white, brittle roots and by thousands of tiny seeds that travel far. Those roots can run more than a foot underground and snap when you try to dig them, with every fragment capable of growing a new plant. Even heavy mulch or landscape fabric won’t stop it. Before long, it weaves through perennials, lawns, and cracks in sidewalks. In northern U.S. states and across southern Canada, it’s now a serious invasive problem, choking out native bellflowers and meadow plants alike.

A Better Alternative: Harebell (Campanula rotundifolia).

If you love that delicate, nodding bluebell look, harebell gives you all the charm without the chaos. It’s a North American native with slender stems, fine foliage, and sky-blue bells that sway in the breeze from early summer into fall. Unlike its invasive cousin, harebell grows in neat clumps, reseeds lightly, and never becomes a pest. It’s also deer-resistant, drought-tolerant, and thrives in lean, well-drained soil.

7. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium and hybrid cultivars)

Yarrow has long been a staple in low-maintenance gardens — feathery foliage, drought tolerance, and endless flat-topped blooms that butterflies love. The trouble is, not all yarrows are created equal. Many of the hybrid and European forms sold in garden centers (Achillea millefolium cultivars like ‘Paprika,’ ‘Moonshine,’ and ‘Summer Pastels’) are far more aggressive than their reputation suggests.

They spread by tough underground rhizomes and self-seed freely, especially in sunny meadows or lightly managed beds. Once established, their dense mats can push out native wildflowers and grasses, reducing diversity in pollinator plantings. Even frequent deadheading doesn’t fully stop them from creeping. In the Midwest and Northeast, they’ve become persistent invaders in naturalized areas — a tough weed in pollinator gardens that started with the best of intentions.

A Better Alternative: Anise Hyssop (Agastache foeniculum).

If what you love about yarrow is that fine, ferny texture and reliable pollinator activity, anise hyssop offers all that — without the takeover. Its fragrant foliage, upright spikes, and long bloom season bring the same soft movement to borders and meadows, but it stays neatly clump-forming. Bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds can’t get enough of its lavender-purple blooms, and deer usually stay away thanks to the minty scent.

8. Bishop’s Weed (Aegopodium podagraria)

If there were ever a plant that lures you in with false promises, it’s bishop’s weed — also sold as goutweed or snow-on-the-mountain. Those green-and-white leaves look cheerful and tidy, brightening shade and filling bare spots under trees where little else seems to grow. It’s deer-resistant, tough as nails, and shrugs off neglect. Sounds ideal, right?

Unfortunately, bishop’s weed doesn’t know when to stop. It spreads by fast-moving underground rhizomes that form a dense, tangled web just beneath the soil. Once it gets going, it can travel under fences, pop up in lawns, and smother everything in its path. Even small root fragments left behind after pulling can regrow — which makes removal nearly impossible without full excavation. In many regions, especially across the Northeast and upper Midwest, it’s become a serious woodland invader, pushing out native ferns and spring wildflowers.

A Better Alternative: Golden Groundsel (Packera aurea).

If you love the look of bright foliage that wakes up shady beds, golden groundsel gives you that same lush, fast cover — without the invasion. Its heart-shaped basal leaves form a dense, deer-resistant carpet through spring and summer, and in late spring, it bursts into clusters of golden-yellow daisies that pollinators adore. It spreads steadily but controllably, creating a natural, living mulch that holds soil and suppresses weeds.

9. Ligularia (Ligularia dentata, L. przewalskii)

Ligularia is one of those plants that seems too good to be true for shaded, damp gardens — and in a way, it is. With its oversized leaves and tall yellow flower spikes, it fills a niche few perennials do: bold, deer-proof structure in part shade. It thrives in rich, moist soil and brings that tropical look northern gardeners love. But in the right conditions, it can turn aggressive.

Species like L. dentata (‘Britt-Marie Crawford,’ ‘Othello’) and L. przewalskii spread by shallow rhizomes that steadily extend outward each season. Given consistent moisture, they form dense colonies that outcompete neighboring plants and self-seed readily. In cooler, wetter regions of the Midwest and Northeast, ligularia has begun escaping cultivation into riparian and wet meadow habitats — areas already sensitive to competition from non-native ornamentals. While not yet classified as a regulated invasive, it’s considered an “emerging invasive” in several northern states.

A Better Alternative: Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis).

This North American native gives you the same bold, moisture-loving look and — importantly — the same deer resistance. Its sap contains alkaloids that make it unpalatable, just like ligularia. In rich, consistently moist soil, it forms a tight basal rosette and sends up 3- to 4-foot spikes of scarlet blooms from midsummer to fall. Hummingbirds and native bees swarm to it, and it stays neatly clump-forming rather than creeping through beds.

10. Lily of the Valley (Convallaria majalis)

Few spring flowers carry as much nostalgia as lily of the valley. Those tiny white bells and their unmistakable fragrance can stop you in your tracks. It’s hardy, dependable, and completely ignored by deer — which is exactly why it’s been passed from one gardener to the next for generations. But the traits that make it so tough in a flower bed are the same ones that let it take over wherever it’s planted.

Lily of the valley spreads fast underground through thick, snaking rhizomes. Once it settles in, it starts to move — under fences, into lawns, even into nearby woodland. Those sweet-smelling clumps can turn into solid mats that crowd out everything else. Because every part of the plant is toxic, deer and rabbits won’t touch it, and few insects use it for food, which means it can quietly replace the native plants that pollinators depend on. It’s not just a survivor; it’s a monopolizer.

A Better Alternative: Canada Anemone (Anemone canadensis).

If you love that low, leafy groundcover with simple white blooms, try Canada anemone instead. It has the same fresh spring look and similar clean white flowers, but it plays fair. It’s a native perennial that spreads gently, fills in shady or moist spots beautifully, and still resists deer thanks to its own mildly bitter sap. It won’t choke your garden or wander into the woods — and unlike lily of the valley, it actually supports native bees and early pollinators.

11. Red Hot Poker (Kniphofia uvaria)

Red hot poker earns its name — those tall torch-like blooms in blazing shades of red, orange, and gold can light up any sunny border. It’s heat-loving, drought-tolerant, and deer rarely touch it, which makes it a go-to perennial for dry, open gardens. For a while, it feels like the perfect “low-effort showstopper.”

But in mild coastal climates, especially parts of California and Oregon, Kniphofia uvaria has started to behave less like a well-behaved perennial and more like a self-seeding wanderer. Each bloom spike produces hundreds of seeds, and in frost-free areas those seeds germinate easily along roadsides and hillsides. The plant’s fibrous root system anchors it deeply, making it difficult to remove once it escapes. In some coastal grasslands, red hot poker has begun forming dense patches that edge out native grasses and wildflowers.

A Better Alternative: Blazing Star (Liatris spicata)

If you love that upright structure and hummingbird-magnet color, swap it for Blazing Star (Liatris spicata). It’s a native perennial that offers the same strong vertical line in the garden, only with spikes of glowing purple instead of orange. Liatris forms neat, clump-based tufts rather than wandering by seed, and it’s just as deer-resistant and drought-hardy. Butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds all flock to it, and its deep roots help build soil health instead of disturbing it.

Written By

Amber Noyes

Amber Noyes was born and raised in a suburban California town, San Mateo. She holds a master’s degree in horticulture from the University of California as well as a BS in Biology from the University of San Francisco. With experience working on an organic farm, water conservation research, farmers’ markets, and plant nursery, she understands what makes plants thrive and how we can better understand the connection between microclimate and plant health. When she’s not on the land, Amber loves informing people of new ideas/things related to gardening, especially organic gardening, houseplants, and growing plants in a small space.