Every fall we’re told the same thing. Leaves are garden gold. Don’t waste them. Rake them up, pile them into the compost, and watch them turn into rich food for your soil. It sounds simple, and in many cases it’s true. Oak, birch, and maple leaves break down quickly, feed earthworms and microbes, and even give pollinators a safe place to hide through the winter.

But here’s the part most gardeners don’t hear. Not every tree gives us a gift when its leaves fall. Some trees defend themselves with chemicals that linger long after the leaves decompose, quietly poisoning soil life and stunting tender crops. Others shed foliage so dense or leathery that it smothers the ground instead of nourishing it. A few carry pests and fungi that settle into your compost or leaf piles and return stronger when spring arrives.

The result is frustration you never saw coming. You think you’re doing right by the garden, only to find tomatoes mysteriously wilting, compost piles that refuse to heat up, or pollinators missing because the “cover” you left was the wrong kind.

If you want your soil healthy, your plants thriving, and your garden alive with bees and butterflies next spring, you need to know which trees drop leaves that cause more harm than good. Here are ten leafy troublemakers whose fallen leaves cause more harm than help and how to handle them wisely.

1. Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

If you only remember one tree to keep out of your compost, let it be the black walnut. These trees produce juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), a well-studied allelopathic compound—meaning it suppresses the growth of other plants. Researchers at Ohio State University have shown that juglone can persist in leaves, husks, and roots long after they’ve fallen, sometimes lingering in compost for a year or more.

What does that mean for you? If you compost walnut leaves and spread them later, your tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, hydrangeas, and azaleas may mysteriously wilt, yellow, or collapse. That’s juglone at work—it interferes with how plant roots breathe, essentially starving them of energy. Unlike oak tannins or pine needles, which microbes neutralize quickly, juglone is remarkably stable and resists the heat of a typical backyard pile.

It’s not just compost you need to worry about. Raked walnut leaves left in garden corners or piled as mulch can leach juglone into the soil over winter. And unlike oak or birch leaves that shelter overwintering butterflies and moths, walnut litter is hostile to pollinators and soil life. Very few insects can safely use it, so leaving it as “wildlife cover” actually reduces habitat.

Best practice: keep every part of black walnut—leaves, nut hulls, roots, and even sawdust—out of compost and out of wildlife piles. Bag them for municipal yard waste pickup, or move them well away from edible beds and pollinator habitats.

2. Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.)

If you’ve ever crushed a eucalyptus leaf between your fingers, you know how strong those oils are. That same fragrance comes from volatile compounds like cineole and terpenes, which act as natural antimicrobials. Great for deterring insects, yes—but a serious problem when those leaves land in your compost pile.

Here’s why: eucalyptus oils don’t just smell nice; they actually slow microbial activity. A healthy compost pile relies on bacteria and fungi working quickly to break down organic matter. Add too many eucalyptus leaves, and you essentially “disinfect” your pile, making it sluggish and sometimes smelly. Studies in soil microbiology have shown that these oils can reduce decomposition rates and even suppress seed germination when the compost is spread later.

On top of that, eucalyptus leaves are waxy and tough. They don’t break down nearly as fast as maple or birch leaves, often persisting in a half-decayed state for months.

Best practice: If you have a eucalyptus tree dropping leaves, don’t treat them like free compost material. Instead, use them in small amounts as a pathway mulch (their oils can help deter pests and weeds there) or send them off in yard waste bins. Just keep them away from the pile that feeds your vegetable beds and flower borders.

3. Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)

At first glance, black locust doesn’t seem like a problem tree. Its creamy spring flowers smell sweet, and the wood is famously rot-resistant. But the leaves it drops in fall come with baggage you don’t want in your garden.

The entire tree—bark, seeds, and foliage—contains toxic compounds such as robinin and lectins, which are poisonous to humans and livestock if ingested. Those same toxins don’t just vanish when the leaves fall. If you compost them, they can carry over into your soil. And if you rake them into a pile and leave them sitting at the back of the yard, the toxins may still leach as they break down.

For pollinators and beneficial insects, black locust leaf litter is especially unhelpful. Unlike the leaves of oaks or maples, which shelter overwintering butterflies and moth pupae, locust leaves are small, thin, and tend to dry into mats that break apart easily. They don’t provide the insulating cover pollinators need to survive winter. On top of that, these trees are prone to fungal leaf spots. Raking and bagging leaves is important, because the fungi can overwinter in the litter and re-infect the tree—and nearby plants—the following season.

Best practice: Keep black locust leaves, bark, and seed pods out of compost and out of pollinator piles. Rake them up and send them with yard waste collection, or discard them far from your growing spaces.

4. Butternut (Juglans cinerea)

Butternut is a close cousin of the black walnut, and unfortunately, it carries many of the same problems when it comes to fall leaves. Like its relative, butternut produces the allelopathic compound juglone, which can linger in fallen leaves, nut husks, roots, and even sawdust.

The chemistry works the same way: juglone interferes with plant respiration, causing sensitive species—especially tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, rhododendrons, and hydrangeas—to yellow, wilt, and eventually collapse. Researchers have noted that juglone can remain active in compost for up to a year or longer, meaning even “well-rotted” piles may still harm your plants.

And it’s not just the compost bin. If you rake butternut leaves into piles around the yard or leave them as mulch, those toxins can leach into the soil, reducing microbial activity and discouraging pollinators and beneficial insects from using the litter for winter shelter. Unlike oak or birch leaves that support moth and butterfly cocoons, butternut debris is effectively a “dead zone” for wildlife.

Best practice: Treat butternut leaves the same way you would black walnut. Keep them out of compost and away from garden beds or pollinator habitat. Bag them for municipal collection or dispose of them at a safe distance from growing areas.

5. Horse Chestnut / Buckeye (Aesculus hippocastanum, Aesculus glabra)

Those glossy “buckeyes” kids love to collect aren’t just for fun—they, along with the leaves, contain aesculin and saponins, chemicals that make the entire tree toxic if eaten. That same chemistry is what makes horse chestnut and buckeye leaves poor candidates for compost. The toxins break down slowly and can linger in the pile, which is the last thing you want ending up around vegetables or pollinator-friendly beds.

The trouble doesn’t stop there. These trees are magnets for leaf blotch and leaf miners, two pests that overwinter in the fallen leaves. Leaving piles on the ground or tucking them into wildlife corners is like rolling out the welcome mat for next year’s infestation. And unlike loose oak or birch litter, horse chestnut leaves are big and leathery—they mat down tightly, smothering the ground beneath and offering little shelter for overwintering insects.

Best practice: Don’t compost and don’t stockpile. Bag and remove horse chestnut or buckeye leaves with your yard waste, or burn them if your area allows. Cleaning them out in fall cuts down disease pressure and keeps those stubborn toxins out of your soil.

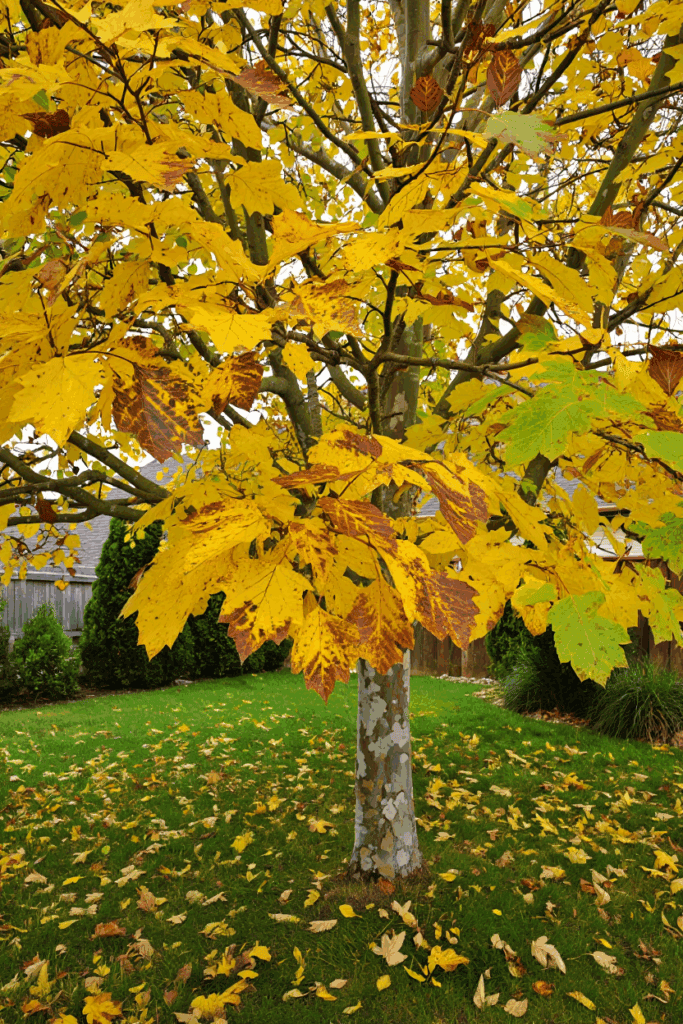

6. Norway Maple (Acer platanoides)

If you’ve got a Norway maple in your yard, you already know how much shade it casts. But here’s what you may not know: the leaves it drops in fall aren’t doing your garden any favors. Unlike native maples, these leaves are loaded with lignin and phenolic compounds—tough plant chemicals that make them break down painfully slow. In fact, researchers have found that Norway maple leaves can take nearly twice as long to decompose as sugar maple leaves.

What happens in your yard? If you leave them where they fall, the big, leathery leaves mat together into a dense, wet carpet. That smothers the soil, blocks air and light, and robs pollinators of the loose, breathable cover they need to overwinter. If you toss them in the compost, they slow the whole pile down and throw off the balance you’re trying to build.

And there’s a bigger story: Norway maples are highly invasive in North America. Their thick leaf litter changes soil chemistry and shades out native wildflowers like trilliums and violets—the very plants early pollinators rely on in spring. In other words, letting those leaves linger in your garden extends the tree’s invasive footprint.

What to do instead: Rake Norway maple leaves promptly. You can shred a few and mix them with “lighter” leaves like birch or ash if you really want to compost, but the bulk is best sent off in yard waste.

7. Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

If you’ve ever raked up a yard full of sycamore leaves, you know how massive they are. A single leaf can be the size of a dinner plate. The problem is, those big leaves don’t break down the way you’d hope. Their tough texture and fuzzy undersides mean they sit around half-decayed, creating a heavy, matted layer that suffocates soil life and blocks pollinators from using the leaf litter for winter cover.

But the real issue with sycamores isn’t just compost—it’s disease and human health. This tree is notorious for anthracnose, a fungal disease that rides out the winter in fallen leaves. Leave them lying around, and you’re basically stocking up spores for next spring’s outbreak. Those tiny hairs and fungal particles can also become airborne when the leaves dry, irritating lungs and skin in a way many gardeners mistake for a simple “dust allergy.”

So while it’s tempting to think of those big leaves as free mulch, they do more harm than good.

What to do instead: Gather sycamore leaves as soon as they fall, and don’t add them to compost or pollinator piles. Bag them up for yard waste or burn them where it’s legal.

8. American Basswood / Linden (Tilia americana)

It’s easy to love a basswood in summer—bees swarm its flowers, the canopy hums with life, and the shade feels like a gift. But in fall, those same trees drop a staggering load of leaves that the ecosystem often struggles to handle.

Unlike the curled, pocketed leaves of oaks that protect overwintering moths and butterflies, basswood leaves are broad and flat. When they pile up, they create a smothering blanket. Soil organisms lose air flow, seedlings beneath them die back, and pollinators that rely on leaf litter for cover simply don’t find shelter there. What looks like natural mulch is, ecologically, a closed door.

Even in compost, basswood litter is heavy and slow to break down, often harboring fungal spots that ride through the winter. In short, instead of cycling nutrients back into the soil food web, these leaves bog it down.

Best practice: Don’t let basswood leaves build up unchecked. Rake and thin them out, shred lightly if you want a little organic matter, but send the majority to municipal collection.

9. Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua)

Sweetgum trees put on one of the most dazzling fall shows in the eastern U.S.—fiery reds, oranges, and purples all on the same branch. But when the leaves and seed balls start dropping, the picture isn’t as pretty for your garden.

The leaves themselves are high in tannins and waxy cuticles, which slow decomposition and make them stubborn in a compost pile. Instead of crumbling down into soft humus, they resist breakdown, especially if added in bulk. Left unraked, they form slick, matted layers that block air and water from reaching the soil. That suffocates soil life and leaves little space for pollinators or beneficial insects to overwinter.

And then there are the infamous spiky seed pods. Not only are they a nightmare underfoot, they’re loaded with resins and can take years to break down, making them a poor addition to compost. Their sharp spines also make leaf piles inhospitable to wildlife that would otherwise shelter in fall litter.

Best practice: Rake up sweetgum leaves and seed balls promptly. Shred small amounts of leaves if you want to blend them into a hot compost pile, but don’t count on them as your main “brown” material. Bagging or sending them with yard waste is the simplest way to keep both your compost system and your soil biology healthy.

Written By

Amber Noyes

Amber Noyes was born and raised in a suburban California town, San Mateo. She holds a master’s degree in horticulture from the University of California as well as a BS in Biology from the University of San Francisco. With experience working on an organic farm, water conservation research, farmers’ markets, and plant nursery, she understands what makes plants thrive and how we can better understand the connection between microclimate and plant health. When she’s not on the land, Amber loves informing people of new ideas/things related to gardening, especially organic gardening, houseplants, and growing plants in a small space.